- Home

- Mickey Spillane

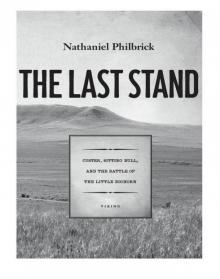

The Last Stand Page 11

The Last Stand Read online

Page 11

By the time it got dark, the Superstitions still didn’t look any closer. Pete thought they ought to stop and take a break and Joe was the first to agree with him. Pete went out and found some firewood, laid it on the sandy ground and said, “You got any matches?”

“I don’t smoke.”

“Didn’t ask you that.”

“Got a lighter, though.”

“What for if you don’t smoke?”

“Boy Scout motto. Be Prepared.”

“Smart, you white guys. Too bad Custer wasn’t that sharp.”

CHAPTER 2

They spotted Pete’s horse in the morning, as the sun came up. It was standing in the vast space between the campfire and the mountain range, the saddle still square on its back and the reins hanging droopily under its chin.

Joe said, “That your horse?”

Pete nodded. “Yeah.”

“Then go get him.”

“You kidding? It’s too late now. That crazy bronc isn’t about to let me get near him without a nosebag full of feed.”

When they stamped the fire out and kicked sand over the embers, they looked down at the horse. The animal gave a great shake, stared right back at them and waited.

“Now what?” Joe said.

“We go,” Pete told him.

“Where?”

“To the mountains. We follow that horse, we’ll end up pawing at the ground to get a drink.”

“I thought you said he knew the way out of here.”

Pete pointed at the mountains. “That’s the way out of here.”

The green shoots sprouting out of the earth only covered a couple of yards, but Pete zeroed right in on that little patch and, with almost a swimming motion, parted the sand, watching the color change from dampness into wetness until he was able to squeeze out two full cupfuls of water from the little oasis. After a half hour, they had another cupful of beautiful liquid that no flatlander could ever have believed was there at all.

Pete licked his lips and asked, “Good?”

Joe nodded. “I’m glad I met me a real Indian.”

“White-eyes, you’re crazy. You don’t know me at all.”

“Sure I do,” Joe told him. “You ride a horse you lost. I fly an airplane that conked out on me.”

“So we’re both losers,” Pete said.

The two looked at each other and Joe flipped Pete a candy bar he had in his pocket. “No way,” he said. “Another forty miles and we have it locked. Think it’ll take us long?”

“You got something else to do?” Pete said.

“Not really.”

“So let’s move.”

Before the sun went down the hunger set in and had it not been for the exquisite tiredness that wanted to melt his body down to nothingness, Joe would have been tempted to dine on the sand and the few ants he had seen scurrying about on the top of the tiny wind-driven dunes.

But Pete had shaken his head. “Come on, Joe. Ants are for chocolate covering and serving at tea parties.”

“You ever have them?” Joe asked him.

“No.”

“Then don’t come to conclusions until you’ve tried them.”

“You ever eat them?”

“No.”

“Want to try?”

“No.”

“White-eyes, you’re going to die of starvation.”

“Yeah? I got another candy bar in my pocket.”

“Halfsies,” Pete said.

Joe broke the Snickers bar in half and handed a hunk to Pete. “Did we do this in the old days?” Joe asked him.

“Nah, we just scalped you suckers and took everything away from you.”

To the south, the horse, which had been pacing them all day, whinnied and didn’t sound lost at all. It didn’t sound thirsty and it didn’t sound hungry, but there was something plaintive about the sound it made. Pete said, “Crazy cayuse, trying to smell up a mare.”

“You think he’ll find one?”

“Sure. He’s luckier than you, White-eyes.”

“I’m not looking.”

“You married, skyman?”

“Nope. Almost was, though. She got teed off and left me.”

“Why?”

“I bought an old airplane instead of an engagement ring.”

Pete stretched and kicked some sand around. “I guess them white girls are smarter than I figured.”

* * *

Before the next night fell the Superstitions had gotten larger and darker. The outline of the rocks was clear and the tree line was evident. There was even a different smell in the air, a pine freshness, and twice there was an acrid smell of smoke. Pete sniffed, shook his head in disgust and said, “Tourists. Bagged charcoal. Ever since the government put the highway through they keep coming up looking for the good old days.”

“Like when?”

“Come on, White-eyes, you ought to know tourists.”

“Where I come from, they’re a pain in the butt,” Joe said. “They wear shorts and black street socks in loafers and think they’re at the beach.”

“Hell, man, out here they’re buying up store-made blankets and plastic arrowheads and taking pictures of us Injuns with dirty faces to show the folks back home.”

“Injuns got dirty faces?”

“Only when we see the tourists coming.” For a second Pete cocked his head into the sun and squinted. Joe tried to follow his gaze and saw nothing, until Pete said, “That cayuse of mine is trying to get back in our good graces.”

Joe turned to his left. A couple hundred yards away the still-saddled bronc was standing still, his eyes on the two men, patiently waiting. Joe said, “You going to get him?”

“Hell no. He threw me once already. I’m not going to give him another chance.”

“Why’d he throw you?”

“A snake damn near bit him, that’s why.”

“Oh,” Joe said. “Maybe he’d let me ride him.”

“No way. He’s my horse.”

“Mind if I try?”

“Go ahead. You white-eyes are always just looking to be put down.”

Joe shrugged and gave a half-hearted whistle and the horse’s ears jerked upright. Slowly at first, then a little quicker, the horse cantered over and stopped beside Joe. Very casually, he stepped into the stirrup and swung his leg over the back of the horse.

“You’d better find the steering wheel,” Pete said without looking back.

Joe felt for the reins, slowly looping them over the mount’s head until he had them in his hands. “Now what?” he asked.

“You figure it out,” Pete said. “Do it wrong and that horse will sure let you know it.”

Joe patted the horse’s neck and its head turned to look at him. “He don’t seem dehydrated,” Joe said.

“Course not. He’s an Indian pony. He dug up a puddle for himself or smelled out a trickle or two in a rock pile.”

“Man, this is desert country.”

“It used to be the bottom of the ocean,” Pete reminded him.

“Comforting thought,” Joe said. “How much farther to the Superstitions?”

“A ways. Why?”

“Pal,” Joe said, “I would like to see some leafy vegetation. I don’t have any toilet paper with me.” He frowned at Pete a second and added, “What do you Native Americans use?”

“We air dry, flyboy. What do you guys use in the airplane?”

“Well, for certain emergencies we have a pilot relief tube which is like a funnel on the end of a rubber hose.”

“So what about the other emergency?”

“We land,” Joe told him.

“City critter,” Pete said derisively.

Joe let out a snort and climbed down out of the saddle. “Quit being jealous. Here, you can have your horse back.”

“Forget it.”

“Why?”

Pete didn’t answer him.

“Old Indian pal,” Joe said, “you’re a lousy rider, aren’t you?” When Pete still didn�

�t answer, he added, “That’s why ole Dobbin here threw you, isn’t it?”

A suppressed laugh made Pete’s shoulders twitch. Finally, he said, “Man, I drive a Harley, a big hog that really stirs up dust. Horses and me never did get along unless they were inside big, fat cylinders.”

“Then why ride him out looking for fossils?”

“Because they don’t have gas pumps on sand dunes, White-eyes.”

They grinned at each other and Joe said, “Pal, I’m beginning to think more of Custer all the time.”

“Don’t bother, flyboy. We cleaned his plow. Right now, we’re only waiting to do it again. You got no John Wayne to back you up anymore.” He paused a second and let out a loud snort. “Man, how my sister loved John Wayne on the late show.”

“You have a sister?”

“Hell, I have six. Why do you think I’m looking for fossils? I have to support the whole family. No brothers. Just me. College-educated and all that and I look for fossils to get a quick buck.”

“What do your sisters do?”

“Five go to school. The other one teaches on the rez. She’s the one who’s been in love with John Wayne since she saw her first Western on TV. Keeps waiting for him to make another.”

“That’ll be a long wait, Pete. Doesn’t she know the Duke’s dead and gone?”

“Don’t tell her that. She’ll lay an axe on your skull.”

“I thought you used tomahawks.”

“Axes are better.”

* * *

The shadow of the mountains had moved across the contours of the earth, coming closer to the pair, and before they expected to, they reached a strange outcropping of rock that was wet on the south side. The horse had smelled it first, edging that way, and the two men, after hearing it whinny, held onto the reins and followed the horse’s lead.

There was no gushing outpour, but a steady dribble that was like the slow flow from a household tap.

They let the horse drink first. It tried lapping at the face of the rock, then pawed at the ground and opened up a hole that filled with water. It satiated itself before giving a mighty shake of its head and drawing back, well-filled.

Joe said, “You first.”

“You ’fraid to drink after a horse?”

“Just being polite.”

Pete shrugged, cupped his hand and drank from his palms. When he was finished, Joe took his turn. It took another hour, but they cooled off and bathed down before the night came on them. Pete took the saddle off the horse, used the blanket to cover them, and they squirmed down into the sand.

Joe asked, “Any ants around here?”

“Just scorpions,” Pete told him. “Go to sleep.”

* * *

A rim of light barely touched the horizon when Pete shook Joe awake. They each had half a Snickers bar and filled themselves with water before heading toward the mountain again. Both men licked the remnants of chocolate from the candy wrapper, knowing this was the last edible they had.

Joe peered through the dim light and asked, “How far away are we?”

“Could be four days’ walk. Maybe one.”

“You’re real encouraging. If it’s four, what do we eat?”

“Ever try snake?”

“Never.”

“Let me ask you a question, flyboy. Would you?”

Joe said, “Let me ask you a question, redskin. Would you?”

Pete shook his head. “I’m college-educated, flyboy. I eat out of cereal boxes and cans. Sometimes a TV dinner.”

“We’re in real trouble, aren’t we,” Joe said.

“You’d better believe it,” Pete told him. “That is, unless it isn’t a four-day walk.”

Pete gathered the reins of his horse in his hand and they started out.

CHAPTER 3

They were a strange trio, two men and a horse. The only thing that tied them together was the survival instinct. None were worn out, no desperation in their movements, but they knew that there could be no faltering, either.

It was a full day later before Joe looked over at Pete, suddenly feeling a new source of encouragement. They’d walked through the night, and as the sun rose he saw that the mountain range they called the Superstitions was large enough and near enough that for the first time he felt sure they could make it.

Bluntly, Joe asked, “How far now?”

“Tomorrow,” Pete grunted. He pointed to the track of a sidewinder rattler in the sand and added hoarsely, “Can you go that long without eating, paleface?”

“Absolutely.”

Then the horse let out a soft whinny, ears pointed straight up and nostrils flared. Pete said, “Water.”

The horse trotted off at an angle. Twice he halted and looked back, and when the pair started to follow him, he edged forward. Twenty yards ahead he stopped.

What looked like a small rise in the desert floor was deceiving. Seasonal winds had hidden another rock outcropping, and on the north side, the sands were wet. Where droplets of water shimmered, small animals had been drinking until the horse’s feet, pawing at the area to bring up the water, had scattered them.

Neither Joe nor Pete minded the horse’s nose nudging them while they drank. Nor was there competition between them, just the sheer pleasure of knowing they could stay alive for the final stretch to the mountains. The morning was wearing on, but they lingered by the water source, resting up, taking that final sip, then angling back toward the mountain range again.

The sun had started on its downward trend when a small cloud cover moved in, giving them shade, and the trio paused, still breathing the heat but not being subjected to its full force. The clouds moved slowly and during the break Joe squatted near a patch of scrub, noting some small animals watching him from several feet away. Apparently humans were new to them, but represented no threat at all. The horse stood comfortably spraddle-legged with Pete squatting in its shadow. He seemed to be chewing and Joe wondered if he had decided to eat a lizard after all. There were enough of them around.

Idly, he kicked at the sand and that small movement uncovered three whitened forms, nearly identical in shape and size. Joe had seen rib bones before and with the toe of his shoe he pried up half a skeleton of some long dead animal he didn’t recognize. He was about to cover it up with sand again when he saw something that wasn’t bone, reached down and dislodged it from its position. He knew what it was immediately: an arrowhead. The tip of it was still embedded in a rib a good half inch until he pulled it out.

Even arrowheads weren’t unfamiliar to him, but this one was unusual. It was delicately formed from some clear material, about two inches long, serrated beautifully along its sides and balanced almost to perfection. The deadly point was still needle sharp and when Joe ran his finger across the edges, it had a sharpness like a razor blade. There was no spur of a shaft at all, but that would have been of a wooden material long since disintegrated by the desert weather.

Joe dropped his find in his breast pocket and walked back to where Pete and the horse waited. Overhead, the edge of the cloud cover was about to let the afternoon light through and it was time to start walking again.

Ahead were the Superstitions. Now they were within reach. Each hour made the central mountain loom larger and before they reached its base the foothills were there and the plants that Pete knew, so that they had something to eat again, and the horse had green, if limited, fodder. And when they had all settled down that night there was no talk of their trek, no talk at all of their ridiculous, unsupervised, unplanned walk across a forbidding stretch of land, no talk at all about their extraordinary find of watering places. The desert is filled with such things if you only look for them.

The three nestled down in the slope of the mountainside; quiet now because safety didn’t need much discussion. The horse was still nibbling at an outcropping of bushes and Pete and Joe were laid back in comfortable hollows watching the sun set.

Pete said, “We made it.”

“Yeah.”

&nb

sp; “What do you do now?”

“Look for a telephone,” Joe told him. He reached into the pocket of his shirt. He fingered out the arrowhead and handed it to Pete. “Okay, college boy, let’s see what you know about this.”

Idly, Pete took it in his hand. His fingertips felt the surface of it and when he ran his finger along its edge blood welled up and he sat up straight. For the first time, he looked at it closely, examining the clear form of the arrowhead, and when he was finished, he sat back and was silent for a long time.

“Damn,” he said.

“What?” Joe asked.

“I’m the fossil hunter,” Pete told him, “and you’re the one who comes up with the big find. Damn. This arrowhead is priceless, man!”

“That’s ridiculous.”

“You know what it’s made of?”

“Nope.”

“Neither does anyone else. Look at it…clear as glass.”

“So?”

“Flyboy, here is a college-certified Indian, a respected and well-thought-of fossil hunter who has come up with some museum-quality artifacts in his short career, and you, a flyboy white-eyes who dropped down into the desert, hands him the greatest find of all.”

“Hell, Pete, don’t come unglued. It’s only an arrowhead. It hit an animal and the animal ran with the thing still in it until it died. What’s the big deal?”

Gingerly, Pete fingered the artifact, turning it over in his hand, inspecting every detail of it, then said, “Joe, no exaggeration, this is the find of the century.”

Joe grimaced. “You can have that damn arrowhead. It’s yours. I don’t want it.”

Very seriously, Pete said, “My friend, you don’t know what you’re giving away.”

“Pal,” Joe told him, “I don’t care. If you like it so much, you can have it.”

“You sure?”

“Absolutely. Why, what’s it really worth?”

“Collectors have offered a couple million bucks if anyone found one.”

“Why? It’s only an arrowhead.”

Pete said quietly, “That little piece of a native mineral is an absolute rarity. Only traces of it have been found. Do you know who the Anasazi were?

Hot Lead, Cold Justice

Hot Lead, Cold Justice Primal Spillane

Primal Spillane Last Stage to Hell Junction

Last Stage to Hell Junction Shoot-Out at Sugar Creek (A Caleb York Western Book 6)

Shoot-Out at Sugar Creek (A Caleb York Western Book 6) The Killing Man mh-12

The Killing Man mh-12 The Body Lovers

The Body Lovers Kiss Me Deadly

Kiss Me Deadly The Long Wait

The Long Wait The Legend of Caleb York

The Legend of Caleb York The Mike Hammer Collection, Volume 1

The Mike Hammer Collection, Volume 1 Dead Street hcc-37

Dead Street hcc-37 The Girl Hunters

The Girl Hunters The Deep

The Deep It's in the Book

It's in the Book The Big Kill mh-5

The Big Kill mh-5![[Mike Hammer 03] - Vengeance Is Mine Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/24/mike_hammer_03_-_vengeance_is_mine_preview.jpg) [Mike Hammer 03] - Vengeance Is Mine

[Mike Hammer 03] - Vengeance Is Mine Kiss Her Goodbye

Kiss Her Goodbye The Big Bang

The Big Bang Delta Factor, The

Delta Factor, The Mike Hammer--King of the Weeds

Mike Hammer--King of the Weeds Kill Me, Darling

Kill Me, Darling The Erection Set

The Erection Set A Long Time Dead

A Long Time Dead Me, Hood!

Me, Hood! Complex 90

Complex 90 The Mike Hammer Collection, Volume 3

The Mike Hammer Collection, Volume 3 The Consummata

The Consummata The Mike Hammer Collection, Volume 2

The Mike Hammer Collection, Volume 2 The Death Dealers

The Death Dealers The By-Pass Control

The By-Pass Control The Snake mh-8

The Snake mh-8 My Gun Is Quick

My Gun Is Quick The Killing Man

The Killing Man Dead Street

Dead Street Killing Town

Killing Town The Last Stand

The Last Stand Black Alley

Black Alley Kiss Me, Deadly mh-6

Kiss Me, Deadly mh-6 Don't Look Behind You

Don't Look Behind You Lady, go die (mike hammer)

Lady, go die (mike hammer) One Lonely Night

One Lonely Night The Will to Kill

The Will to Kill One Lonely Night mh-4

One Lonely Night mh-4 The Big Showdown

The Big Showdown Mike Hammer 09 - The Twisted Thing

Mike Hammer 09 - The Twisted Thing The Mike Hammer Collection

The Mike Hammer Collection The Tough Guys

The Tough Guys Killer Mine

Killer Mine I, The Jury mh-1

I, The Jury mh-1 Vengeance Is Mine mh-3

Vengeance Is Mine mh-3 Everybody's Watching Me

Everybody's Watching Me The Last Cop Out

The Last Cop Out Lady, Go Die!

Lady, Go Die! Survival...Zero

Survival...Zero Survival... ZERO! mh-11

Survival... ZERO! mh-11